By Dipesh Ghimire

Inflation Pressures Ease, But Food Prices Turn Negative

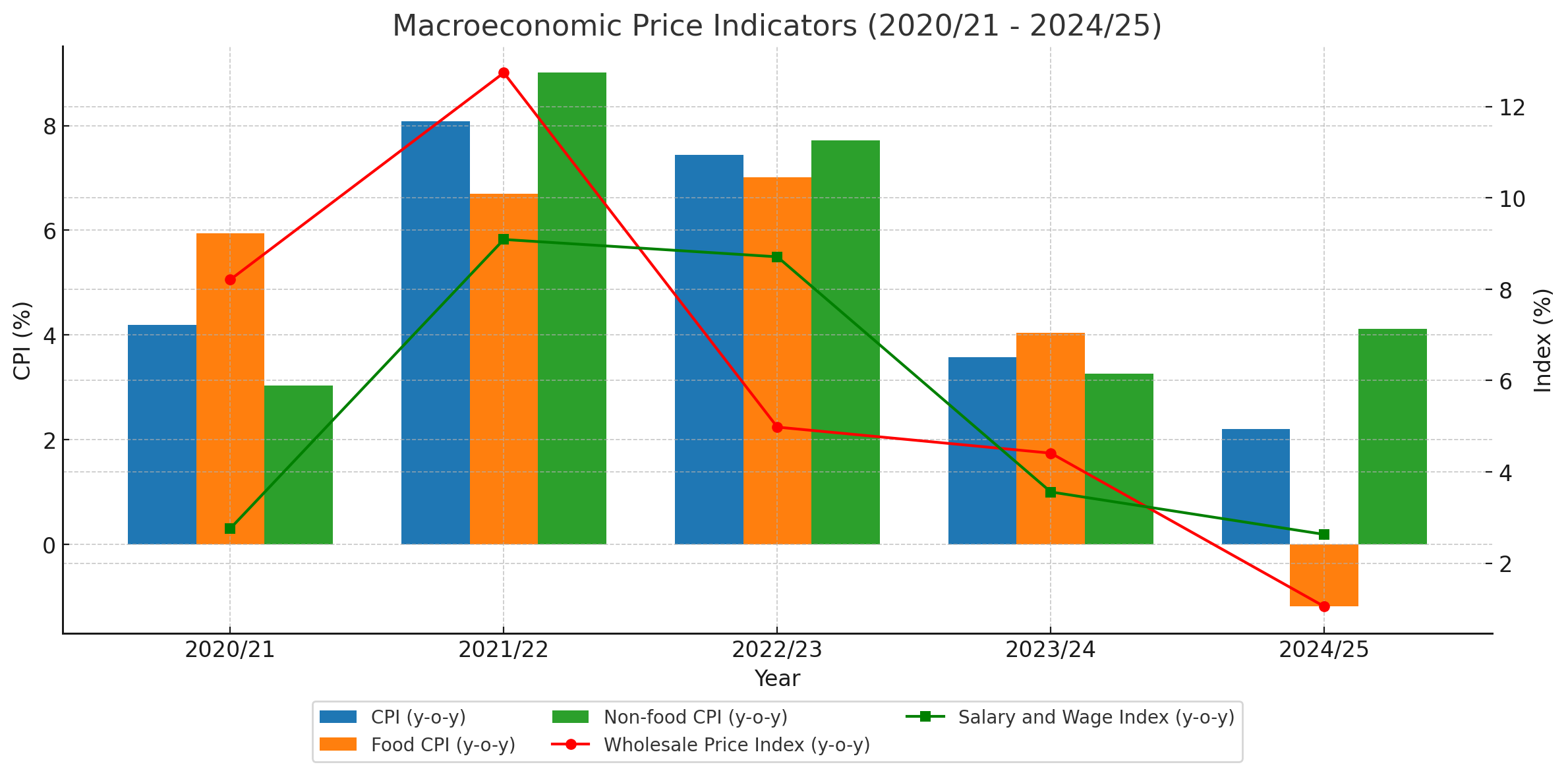

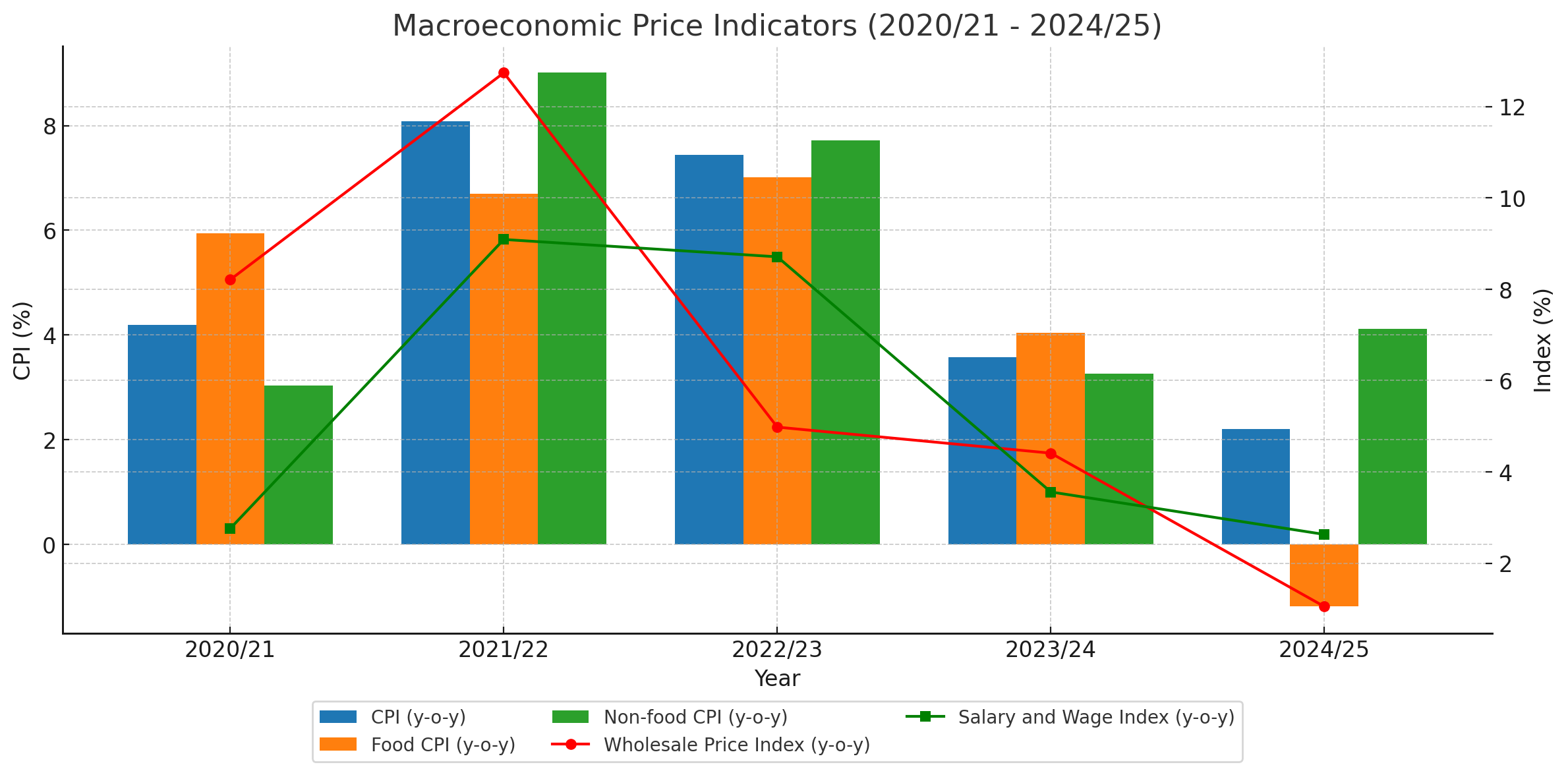

Nepal’s latest macroeconomic indicators reveal a mixed inflationary trend over the past five years, with consumer prices showing a significant cooling in recent years, even as non-food prices remain sticky and food prices unexpectedly slip into deflation in the current fiscal year.

CPI Trend Shows Cooling Inflation

The Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures overall inflation, spiked to 8.08 percent in 2021/22—its highest in the period under review—amid global supply chain disruptions and rising import costs. It moderated to 7.44 percent in 2022/23, and has since eased substantially, falling to 2.20 percent in 2024/25, signaling improved price stability.

The annual average CPI also follows a similar pattern, peaking at 7.74 percent in 2022/23, before settling at 4.06 percent in 2024/25. Economists interpret this decline as evidence of subdued demand, tighter monetary policy, and easing global commodity prices.

Food vs Non-Food Divergence

One striking development is the divergence between food and non-food inflation.

Food CPI surged around 7 percent in 2022/23, but has since collapsed to -1.19 percent in 2024/25, indicating actual deflation in food items. Analysts attribute this to improved domestic harvests, falling global edible oil and grain prices, and stronger import supply.

Non-food CPI, in contrast, has remained elevated, standing at 4.12 percent in 2024/25, with key drivers being housing, utilities, education, and healthcare costs. This structural persistence in non-food inflation suggests households continue to feel pressure outside food-related consumption.

Wholesale Prices Signal Weak Demand

The National Wholesale Price Index portrays a sharper story of slowdown. After climbing by 12.74 percent in 2021/22, it dropped dramatically to 1.05 percent in 2024/25. The annual average too shrank from 9.51 percent in 2021/22 to just 3.84 percent in 2024/25. This steep decline reflects weaker demand from manufacturing and construction sectors, along with reduced import price pressures.

Experts caution, however, that while falling wholesale prices help curb inflation, they also signal sluggish economic activity and weaker bargaining power for producers.

Salary and Wage Growth Weakens

The Salary and Wage Index paints another important picture. After hitting 9.09 percent growth in 2021/22—driven by post-pandemic labor shortages and government salary revisions—it has since cooled, recording only 2.63 percent in 2024/25. The annual average also fell from 9.90 percent in 2022/23 to 2.85 percent in 2024/25.

This indicates that household earnings are not growing in line with costs, especially non-food inflation, putting real income under pressure. Labor unions have already flagged this disparity as a concern for domestic consumption.

Interpretation: Stability or Stagnation?

Overall, the data suggests that Nepal has moved from a period of high inflationary stress (2021/22–2022/23) to a phase of relative price stability (2023/24–2024/25). However, this easing comes with caveats:

Food price deflation may benefit urban consumers but could hurt farmers and rural producers.

Sticky non-food inflation continues to squeeze household budgets, especially given slower wage growth.

Weak wholesale prices highlight potential stagnation in productive sectors.

Economists say the challenge for policymakers is to balance inflation control with growth revival. If wages stagnate while non-food costs remain high, household purchasing power may erode, dampening consumption—the backbone of Nepal’s economy.